Article reviewed and approved by Dr. Ibtissama Boukas, physician specializing in family medicine

Fractures of the atlas, the first cervical vertebra (C1), represent 2 to 13% of acute injuries of the cervical spine and 1-2% of all spinal injuries. Also called Jefferson fractures, these injuries are caused by traumatic axial loading, and are usually associated with other injuries of the upper cervical spine. Violent rotational forces on the head and neck can also cause atlas fractures in rare cases.

This article of Jefferson's fracture, from diagnosis to conservative and surgical treatment options to correct this disorder.

Definition and Mechanism of Injury

A Jefferson fracture is a bone fracture of the C1 vertebra. The C1 vertebra is a bony ring, with two lateral wedge-shaped masses, connected by relatively thin anterior and posterior arches and a transverse ligament.

The lateral mass of the higher C1 vertebra is directed laterally. Consequently, vertical forces compressing the lateral masses between the occipital condyles and the axis push them apart, fracturing one or both anterior or posterior arches. Impact forces cause C1's lateral masses to spread outward.

A Jefferson fracture does not always result in spinal cord injury because the dimensions of the bony ring increase. A spinal cord injury is more expected if the transverse ligament has also been ruptured.

C1 vertebral fractures occur primarily because the occipital condyles of the skull are forced into the lateral masses of C1. Unless there is a retropulsated bone fragment, patients generally do not have spinal cord injury or neurological deficits because the fracture has propagated outward. However, the vertebral arteries are at high risk of injury (dissection and/or thrombosis) or spasm due to inflammation that can lead to neurological deficits.

Symptoms of the disease

A Jefferson fracture causes pain in the upper part of the neck. Generally speaking, patients do not have major problems with movement, speech, or brain function, unless the nerves in the spinal cord are also injured.

In some cases, the arteries in the neck are damaged. Injuries to blood vessels in the upper neck can lead to neurological complications, such as ataxia. As a reminder, ataxia is a loss of muscle control and balance during walking. Bruising and swelling around the area of injury are common.

Other potential features of a Jefferson fracture include the following signs and symptoms:

- There may be upper cervical pain and stiffness, usually isolated to the area around the fractured vertebra.

- You may have difficulty walking and even breathing if there has been damage to the spinal cord.

- You may feel a lot of pain in another part of your body and not be aware of your neck pain.

If the pain radiates down your spine, into your arms and/or your legs, it is likely that the condition is due to a cervical disc herniation and not a Jefferson fracture (even more so if the cause is not traumatic).

Diagnostic

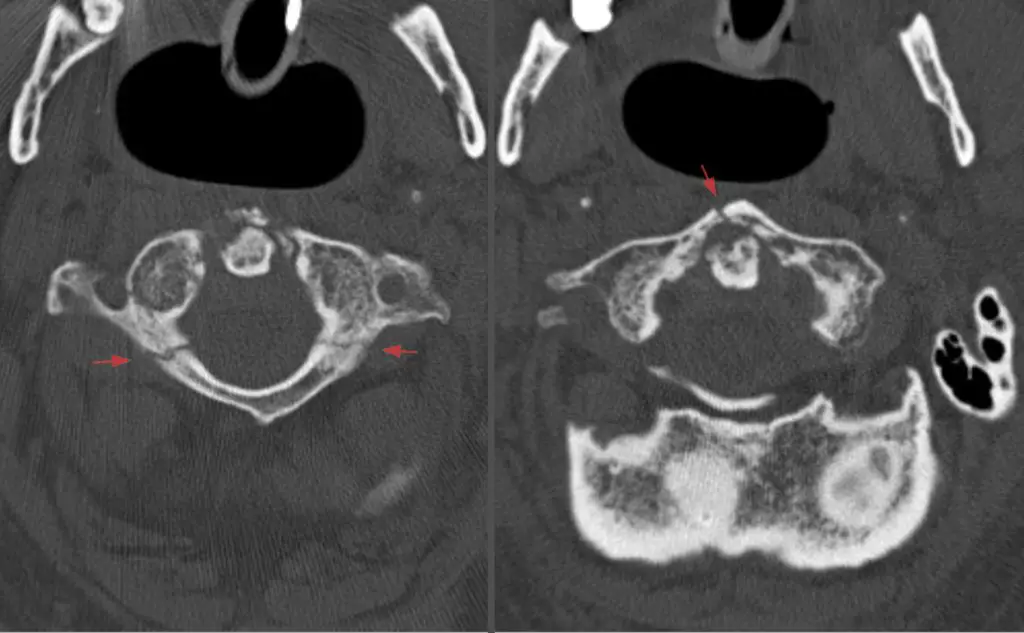

Definitive diagnosis of an isolated fracture often requires computed tomography (CT), while ligament injury is more easily identified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Ligament instability can be recognized on open-mouth radiographs showing a lateral displacement of the mass of 7 mm or more.

The atlanto-dens interval (ADI), defined as the distance between the atlas and the dens, can also be used as a marker of ligament instability. The normal ADI is less than 3 mm, and a greater distance indicates a higher degree of ligament injury.

The use of CT and MRI allows for a more complete assessment of bone injury and a more accurate assessment of atlas-associated ligament structures.

Once identified, atlas fractures can be classified into 4 types of fracture:

- Type I fractures are isolated to the anterior or posterior arch, a rare lesion with an intact transverse ligament.

- Type II injuries, also known as Jefferson fractures, are burst fractures with bilateral C1 anterior and posterior arch fractures.

- Type III fractures involve the lateral mass. Jefferson fractures and lateral mass fractures may be isolated or may be associated with a large ligament rupture.

Treatment

Conservative

The treatment of atlas fractures remains controversial, in part due to the frequency of other cervical injuries associated with these injuries. No standards or guidelines for the treatment of C1 fractures alone or in combination with other cervical spine injuries have been developed. Instead, treatment recommendations for isolated C1 fractures and combined C1-C2 fractures are usually based on a cluster of case series.

Depending on the extent of the trauma, nonoperative treatment consisting of external orthoses is often effective if the fracture is stable. Most isolated C1 fractures and stable C1-C2 fractures are managed with a rigid collar, halo-thoracic corset, or sterno-occipito-mandibular immobilization.

External immobilization is recommended for C1-C2 combination fractures unless instability is evident on standing and supine radiographs while the patient is wearing a brace. An intact ligament can be treated with either a soft or hard collar, while a ruptured ligament without a bone avulsion component may require a traction suit, halo vest, or surgery if refractory to non-operative treatment.

In the majority of cases, a hard collar is adequate treatment. Some clinicians prefer a halo vest or Minerva body vest to avoid further trauma to the injured vertebra by limiting cervical mobility.

Surgical

Surgical treatment of isolated axis fractures is rarely indicated, as immobilization of the neck is usually adequate. The main consideration for surgery is instability, usually assessed using mobility on flexion-extension films.

Using the classification of Anderson and D'Alonzo, type I and III odontoid process fractures are generally considered stable while type II, the most common variant, is unstable.

Another objective indication for surgery includes a confirmed rupture (i.e. using MRI) of the mid-substance transverse ligament and the presence of atlanto-occipital instability. A relative indication for surgery that is not universally accepted is the presence of bilateral displacement of the lateral masses totaling more than 6,9 mm on open-mouth radiographs. A shift of this magnitude suggests rupture of the transverse atlas ligament and associated instability.

A shift of the two lateral masses of the atlas on the axis ranging from 3 to 9 mm can also indicate a Jefferson burst fracture. Although these injuries can initially be treated with rigid immobilization, patients should be monitored for ongoing pain and instability.

Flexion-extension views can be obtained 3 months post-injury to assess any remaining pathological movement indicating ongoing instability. If radiographic signs of instability persist, internal C1-2 fixation can be performed to alleviate neck pain and the risk of serious brainstem and spinal cord injury.

In general, surgery for Jefferson fractures goes as follows:

- Using polyaxial screw fixation of the lateral masses of C1 and pedicle screw or pars fixation of C2. The procedure begins with a midline incision descending from below the inion to just above the subaxial cervical spine. Then a retractor is used to separate the splenius capitis muscles and dissection continues until the posterior arch of C1 and the lamina of C2 are visible.

- After adequate exposure of the bony landmarks, the central and medial sections of the lateral mass are skeletonized to identify the entry point of the C1 lateral mass, taking care to avoid the vertebral artery.

- During this stage, the venous plexus is subjected to cauterization, tamponade, and the application of hemostatic agents. The C2 nerve root can be retracted caudally. The entry point is made 3 to 4 mm laterally from the medial aspect of the lateral mass C1 using a match or an awl.

- The lateral mass is cannulated using a drill pointed at approximately 20° rostral with a minimal midline trajectory. A partially threaded screw is placed with only the smooth part of the instrument abutting against the C2 nerve root. Screws are then placed into the pars or C2 pedicle, with the entry point of the pars screw a few millimeters rostral to the C2/C3 joint and an entry point slightly rostral and lateral to that of the pars screw to a C2 pedicle screw.

- Once the screws are properly placed, their alignment is assessed by lateral and AP fluoroscopy. After confirming proper placement, the stems are cut and secured to the screw tulip heads using set screws.

Prognosis: Is it serious?

C1 fractures are a complex group of upper cervical injuries, and their diagnosis and treatment require a holistic approach. The context of any spinal cord injury in addition to the general health status of the patients (eg: obesity, myelopathy, ability to comply with treatment, osteoporosis, etc.) will dictate treatment methods.

While the majority of these injuries can be treated with nonoperative immobilization, some fracture features require surgical fixation or fusion. The surgeon should be aware of the types of fractures that require further stabilization and monitor patients closely for signs of instability and deformity after nonoperative management.

In short, it is according to the type of fracture that we can determine if it is serious or not.

My name is Anas Boukas and I am a physiotherapist. My mission ? Helping people who are suffering before their pain worsens and becomes chronic. I am also of the opinion that an educated patient greatly increases their chances of recovery. This is why I created Healthforall Group, a network of medical sites, in association with several health professionals.

My journey:

Bachelor's and Master's degrees at the University of Montreal , Physiotherapist for CBI Health,

Physiotherapist for The International Physiotherapy Center